La desigualdad en los países emergentes, 1910-2010 agosto 5, 2014

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.add a comment

Hace tres años que no publicamos…

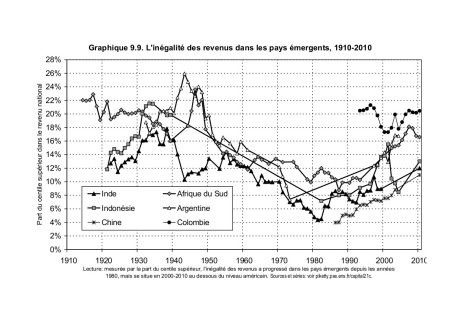

Pero como estamos leyendo el Capital de Piketty, abajo pegamos un cuadro interesante:

En la Argentina, el centil superior se apropia de un 17% del ingreso nacional. Piketty señala que la desigualdad en los países emergentes ha crecido a partir de la década de 1980, pero que para 2010 este nivel se encuentra por debajo del exhibido por los EEUU. Los seis países analizados, entonces, se encontrarían en una categoría intermedia entre las definidas por Piketty como «desigualdad media» (UE) e «desigualdad fuerte» (EEUU) (capítulo 7 de «le capital…»). Aquí, la tabla correspondiente.

London Calling agosto 9, 2011

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.add a comment

When they kick out your front door

How you gonna come?

With your hands on your head

Or on the trigger of your gunYou can crush us

You can bruise us

But you’ll have to answer to

Oh, Guns of Brixton

Para nuestros queridos amigos de Renegade Eye

Egipto febrero 1, 2011

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.add a comment

Nos hemos rendido ante la inevitable pereza veraniega.

Aunque ya estemos idos, todavía no hemos llegado – esta suerte de Purgatorio es insoportable -.

Les dejo la que creemos es la mejor crónica sobre Egipto, escrita un año antes de los sucesos de estos días, en el London Review of Books de mayo de 2010.

Algunos extractos:

It’s still often said that ‘what happens in Egypt affects the entire Arab world,’ but nothing much has happened there in years. Egypt has fallen behind Saudi Arabia – not to mention non-Arab countries like Turkey and Iran – in regional leadership. Even tiny Qatar has a more independent foreign policy. Egypt is by far the largest Arab country, with 80 million inhabitants, yet it’s seen by most Arabs – and by the Egyptians themselves – as a client state of the United States and Israel, who depend on Mubarak to ensure regional ‘stability’ in the struggle with the ‘resistance front’ led by Iran.

Despite the promises of the regime – and contrary to the expectations of Egypt’s sponsors in the West – economic liberalisation hasn’t led to much in the way of political liberalisation: in 1992, the year it adopted an IMF stabilisation and structural adjustment package, Egypt began sending civilians to be tried at military tribunals. The Emergency Law, in force since Sadat’s assassination and recently renewed despite Mubarak’s promise to lift it, grants the government extraordinary powers to arrest its opponents without charge and to detain them indefinitely; there are an estimated 17,000 political prisoners, most of them Islamists.

The ideology of Mubarak’s National Democratic Party has undergone marked shifts in recent years, alternating between Milton Friedman and Muhammad, as the occasion demands. Arab unity, as the novelist Sonallah Ibrahim remarks, has been reduced to the ‘unity of foreign commodities consumed by everyone’.Foreign policy is a particularly anguished subject. While the peace with Israel reached in 1979 by Sadat may make Egypt a ‘moderate’ state in the eyes of Washington, it has left many Egyptians deeply embittered. Mubarak drew a lesson from Sadat’s fate: it was one thing to make a deal with Israel – quite another to make nice. He would honour the peace treaty, but he would not go to Tel Aviv, or engage in ostentatious displays of friendship that would offend Egyptian honour; and he would turn a blind eye to anti-Israel invective in the press, so that opponents of ‘normalisation’ with Tel Aviv could let off steam. By maintaining an appearance of froideur, Mubarak was able to repair relations with the Arab League and with the Arab states that had cut their ties with Egypt in 1979. Meanwhile, he has developed a partnership with Israel on trade and ‘security’ that is far more extensive than Sadat could have imagined. Their intelligence services work closely together, and Mubarak has supplied weapons and training to the Palestinian Authority in its war against Hamas. The government is also doing what it can to maintain the siege in Gaza, concerned that if it opens its border crossing, Israel might shut down all its crossing points and try to dump Gaza in Egypt’s lap, which would be particularly unwelcome given that the Hamas rulers in Gaza are allies both of Mubarak’s domestic opponents, the Muslim Brothers, and of his foreign adversaries, Iran and Hizbullah.

Mubarak was never close to the Brothers, but he has had to find a way to live with them, if only because they are too deeply embedded in society – and in the mosques, no-go zones for the state – to be eliminated. Their status is often described as ‘banned yet tolerated’: ‘banned’, because they would pose a serious threat to the regime if they were allowed to participate freely; ‘tolerated’, because they allow Mubarak to present himself as Egypt’s only defence against an Islamist takeover. Thus, under American pressure to open up Egypt’s political system, Mubarak permitted the Brothers to run in the 2005 legislative elections. To the horror of the liberal opposition, and of the Bush administration, they won 88 of the 160 seats they contested, a fifth of the seats in the lower house of parliament, making them the second most powerful party after Mubarak’s NDP. Since then, the US has all but dropped its pressure on Mubarak to democratise, and the Brothers have had their wings clipped.

Sobre Suleiman

Suleiman, the head of General Intelligence, is both a lieutenant general in the army and a member of Mubarak’s cabinet. He is the second most powerful man in Egypt, a key player in negotiations between Israel and Hamas and one of the most formidable spymasters in the Middle East.

His success in crushing the insurgency – and the dossier he compiled on Egyptian jihadists, many of whom joined Bin Laden after their defeat in Egypt – made him a valued partner for the CIA after 9/11.

Sobre ElBaradei

He has spent most of his professional life in the West; he won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005 for his work with the International Atomic Energy Agency (he donated the proceeds to orphanages in his hometown); and he crossed swords over the inspections in Iraq and Iran with the Bush administration, which tried to force him out of his job. All reasons to respect him. When he flew home from Vienna in February, at the end of his third term at the IAEA, he was greeted at the airport by a thousand supporters. He then met members of the opposition, from Kifaya to the Muslim Brothers, and gave a series of blistering interviews on the state of Egyptian political life. Sounding rather like Obama in 2008, he insisted that he was ‘not a saviour’, that ‘only with the help of the people could he try to change the authoritarian regime in power for the last 50 years’. It’s easy to understand why Egyptians are tempted to see him as a saviour: an outsider, untainted by compromise and unaffiliated with any of Egypt’s political parties, he is someone on whom extravagant hopes can be pinned. Apart from generalities – restoring the rule of law, ensuring social protection for the poor, providing humanitarian aid for Gaza – he has said little about what he would do as president. ‘He remains an unpolitician,’ as the reporter Issandr El Amrani put it.

Y Obama

Egypt, the second largest recipient of US aid after Israel, recently received $260 million in ‘supplementary security assistance’, as well as $50 million for border security, which probably means reinforcing the blockade of Gaza.

Less expensive at any rate than it would be in the event of an Islamist takeover that ‘would pose a far greater threat – in magnitude and degree – to US interests than the Iranian revolution’. This seems to be the Obama administration’s implicit wager, too. It’s bad news for ElBaradei and his supporters: bad news for all the Egyptians who fear that they will never know democracy because of the ‘American veto’.

The almighty markets will punish those who fail… noviembre 18, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in comercio internacional, negociaciones economicas.1 comment so far

De una serie de notas de Paul Krugman en el New York Review of Books

Impresiones junio 20, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.Tags: Argentina; politica exterior

3 comments

Este blog continúa defraudando su objetivo declarado: seguiremos sin postear, incluso cuando se ha producido cambio de Canciller.

Un novel blog complementa lo no producido por La Cola…, desde aquí recomendamos El Adentro-El Afuera, responsabilidad de la pluma del Fatherly Leader.

Algunas primeras impresiones de la salida de Taiana y su reemplazo:

- creer que un mero cambio de personal puede producir virajes radicales es pensar la polex a la manera decimonónica: desde el Congreso de Viena para acá – incluso lo producido por el mismo Congreso – el comportamiento y los resultados están estructuralmente “dados” (incluso Talleyrand y Metternich) – sin que esto signifique un determinismo positivista.

- lo anterior vale para todos: pese a lo que diga 6,7,8, una membrecía como la del G20 o la Cumbre de Seguridad Nuclear trasciende la mayor o menor “muñeca” de un presidente y/o un canciller determinado: es el disfrute de décadas de desarrollo nacional – no menor en la formación de burocracias modernas, ítem ausente en las fuerzas partidarias populares actuales, también en la épica kirchnerista (obvio que no le voy a pedir tal objeto al PRO)

- Que las diplomacias presidenciales, pese a que la encarnen líderes más o menos progres, es un corolario necesario de tal mistificación: Felipe Pigna o Pedro Brieger como los Hippolyte Taine del progresismo. El lado oscuro de esa forma de vinculación externa no es sino el gesto espasmódico y el deslumbramiento momentáneo – materializado en su forma espuria en supuestas diplomacias paralelas.

- Signo actual de dicho deslumbramiento es cierta opinión respecto al Brasil: uno no necesita caer en la desconfianza de Estanislao Zeballos para manejarse con cierta prudencia: desde la búsqueda de un asiento en el Consejo de Seguridad, pasando por su desempeño en los foros de DDHH (compartiendo muchas veces posiciones con lo más reaccionario del asunto, Iran, Cuba y Corea del Norte – yo también lo siento, pero la isla es difícil de defender en la mayoría de las posiciones que adopta en estos temas –), llegando a Iran: viejo, si tu principal aliado no puede reconocerte puntos básicos de tu concepción de polex, que te espera en temas menores…¿Ponerlo como tercero “imparcial”?!!! (el Tratado del río Uruguay nace en el contexto del temor al manejo que podría hacer el estado río arriba (Itaipú, etc)

- Pese a la relevancia de los constreñimientos estructurales, o de su comprensión, lo cierto es que en 2003 hubo toma de posición respecto a las limitadas opciones presentes – y la mayoría de ellas en el sentido que nos gusta en este blog: integración latinoamericana, acento en el multilateralismo, vigorosa promoción de la producción nacional, etc. No obstante, nada distinto a la historia de la Argentina moderna, salvo el paréntesis menemista.

- de algunas palabras de hoy de la entrevista con Página, y de una línea del gran Mario, también hoy, el nuevo Canciller parece venir con los mismos prejuicios troko-leninistas del estado como herramienta: dice Mario: El rol de las cancillerías es, pues, muy arduo y desafiante: darles contexto y profesionalidad a las líneas maestras (y a menudo a las decisiones tomadas de volea) que se cocinan en la cima del poder. Y agrega: peso que tiene la Cancillería, por el sesgo conservador de buena parte de la “línea” de la “Casa”… Y dale con esto, como si fuera distinto al sistema político argentino. Cuando en los 90 se desmalvinizaba – incluido todo el arco político -, o se creía en la bondad natural del sistema económico internacional – también toooodooo el sistema político nacional –, grises y conservadores burócratas le buscaban la vuelta para que los efectos de tales decisiones fueran menos nocivas. Siempre hay un progre que pueda hacer el papel iluminado de un Cisneros, esperemos que no en esta oportunidad.

- Al nuevo Canciller, le deseamos una buena gestión.

Si dejás un territorio huérfano de comunicación… abril 27, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.add a comment

Adherimos.

Tailandia: queseaelvientoelquenferme… abril 10, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.Tags: Asia, Crisis Política, Tailandia

add a comment

Volvemos al primer amor. Vuelve nuestra crisis preferida.

Aunque parece un poco exagerado esto del «Día del Juicio Final» – y eso que el BP es el diario capitalino en inglés más cercano a los Camisas Rojas –

Insistimos en lo que decíamos acá, acá y acá.

La crisis política en Tailandia lleva un par de años, pero el capítulo más reciente se inicia con la vuelta de un gobierno democrático, a fines del 2007, luego del breve interregno militar.

¿Qué explica tal empate? Básicamente, la pérdida de poder político por las elites urbanas – Bangkok – a manos de nuevas elites que han construido su legitimidad en base a apelar a las masas rurales con un discurso – a falta de mejor palabra, y con las salvedades laclauescas – populista. A partir de la elección de 2001, la primera relativamente libre y limpia, la población rural ha votado mayoritariamente a estas contra elites (?) para desesperación de las iluminadas clases medias de Bangkok.

Del gobierno de los jueces… marzo 9, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.Tags: EEUU

2 comments

No sé si esto lo habrá levantado alguien, pero me parece relevante – al menos a mí, perseguido, al igual que José Rizal, por el espectro de las comparaciones (aunque en Noli me Tangere la frase sea el fantasma de las comparaciones) -.

En Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, la mayoría conservadora de la Corte Suprema de Justicia de los EEUU rechazó jurisprudencia bien establecida y hace peligrar la vigencia de legislación nacional y estadual que se remonta a 1907 (de la era de las leyes antitrust del Roosevelt bigotón), al permitir que las corporaciones puedan gastar sin límites en propaganda política en tiempos de elecciones.

El Tony Blair de este lado de la Mar Oceánica no la dejó pasar. En el Discurso sobre el Estado de la Unión, dijo:

Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests—including foreign corporations—to spend without limit in our elections.

Pese a que los Supremos Yankees tienen una sana tradición de blanqueo de sus simpatías políticas, con esta se fueron a la miércoles con la autolimitación de los togados.

¡Y pensar que cuando purrete el Oyhanarte jóven – y onganista – me parecía un embole!

Como Joaco no la va contar – o si lo hace usará el argumento tailor-made que escuchará en algún copetín (de dorapa, como corresponde a la práctica; mi gato me dice que se le hace mucho más creíble la imagen del tipo haciendo un anacrónico kowtow) por el cuál este fallo en realidad está en línea con la Primera Enmienda (free speech) -. Le paso la bola a Gustavo Arballo para que ilumine sobre la endeblez de ese argumento.

Desde aquí se puede bajar el fallo completo en PDF.

Kemalismo marzo 5, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.Tags: Armenia, EEUU, genocidio, I Guerra Mundial, Turquía

add a comment

Seguimos huyendo de la coyuntura.

Aprovechamos la aprobación de una moción de la Comisión de Asuntos Exteriores de la Cámara de Representantes de EEUU, que califica de «genocidio» la matanza de armenios por las fuerzas turcas en la Gran Guerra, para colgar el mejor resumen que hemos podido encontrar en formato electrónico sobre el período. Le robamos hasta el título a la pieza de Perry Anderson.

Expulsada de Europa, la Turquía de los Jóvenes se lanzó sobre el Cáucaso: la derrota – menos de un séptimo de las tropas regresaron – dejó expuesta a la retaguardia y al país: el espacio que separaba ahora a los Aliados de Turquía era habitado por los súbditos armenios del Imperio Otomano que se desgranaba…

In Istanbul, the CUP reacted swiftly. This was no ordinary retreat into the kind of rear where another Battle of the Marne might be fought. The whole swathe of territory extending across both sides of the frontier was home to Armenians. What place could they have in the conflict that had now been unleashed? Historically the oldest inhabitants of the region, indeed of Anatolia at large, they were Christians whose Church – dating from the third century – could claim priority over that of Rome itself. But by the 19th century, unlike Serbs, Bulgars, Greeks or Albanians, they comprised no compact national majority anywhere in their lands of habitation. In 1914, about a quarter were subjects of the Russian, three-quarters of the Ottoman Empire. Under the tsars, they enjoyed no political rights, but as fellow Christians were not persecuted for their religion, and could rise within the imperial administration. Under the sultans, they had been excluded from the devshirme from the start, but could operate as merchants and acquire land, if not offices; and in the course of the 19th century they generated a significant intellectual stratum – the first Ottoman novels were written by Armenians…

The CUP’s immediate fear, as it surveyed the rout of its armies in the Caucasus, was that the local Armenian population might rally to the enemy. On 25 February, it ordered that all Armenian conscripts in its forces be disarmed. The telegrams went out on the day Anglo-French forces began to bombard the Dardanelles, threatening Istanbul itself. Towards the end of March, amid great tension in the capital, the Central Committee – Talat was the prime mover – voted that the entire Armenian population in Anatolia be deported to the deserts of Syria, to secure the Ottoman rear. The operation was to be carried out by the Teskilât-i Mahsusa, the ‘Special Organisation’ created for secret tasks by the party in 1913, now some 30,000 strong under the command of Bahaettin Sakir…

The enterprise on which the CUP embarked in the spring of 1915 was, however, new. For ostensible deportation, brutal enough in itself, was to be the cover for extermination – systematic, state-organised murder of an entire community. The killings began in March, still somewhat haphazardly, as Russian forces began to penetrate into Anatolia. On 20 April, in a climate of increasing fear, there was an Armenian uprising in the city of Van. Five days later, Anglo-French forces staged full-scale landings on the Dardanelles, and contingency plans were laid for transferring the government to the interior, should the capital fall to the Entente. In this emergency, the CUP wasted no time. By early June, centrally directed and co-ordinated destruction of the Armenian population was in full swing. As the leading comparative authority on modern ethnic cleansing, Michael Mann, writes, ‘the escalation from the first incidents to genocide occurred within three months, a much more rapid escalation than Hitler’s later attack on the Jews.’ Sakir – probably more than any other conspirator, the original designer of the CUP – toured the target zones, shadowy and deadly, supervising the slaughter. Without even pretexts of security, Armenians in Western Anatolia were wiped out hundreds of miles from the front…

Çaglar Keyder has described the desperate retroactive peopling of Anatolia with ur-Turks in the shape of Hittites and Trojans as a compensation mechanism for the emptying by ethnic cleansing at the origins of the regime. The repression of that memory created a complicity of silence between rulers and ruled, but no popular bond of the kind that a genuine anti-imperialist struggle would have generated, the War of Independence remaining a small-scale affair, compared with the traumatic mass experience of the First World War. Abstract in its imagination of space, hypomanic in its projection of time, the official ideology assumed a peculiarly ‘preceptorial’ character, with all that the word implies. ‘The choice of the particular founding myth referring national heritage to an obviously invented history, the deterritorialisation of “motherland”, and the studious avoidance and repression of what constituted a shared recent experience, rendered Turkish nationalism exceptionally arid.’…

Picadilly Circus Chainsaw Massacre marzo 4, 2010

Posted by Lodovico Settembrini in El Reino de este Mundo.Tags: crisis económica, Europa, Reino Unido

add a comment

Solía pensar que si existiera la reencarnación, me gustaría regresar como el Papa, o el Presidente…, pero ahora querría retornar como el mercado de bonos. Podés intimidar a todos…

Cuts of that magnitude have never been achieved in this country. Mrs Thatcher managed to cut some areas of public spending to zero growth; the difference between that and a contraction of 16 per cent is unimaginable. The Institute for Fiscal Studies – which admittedly specialises in bad news of this kind – thinks the numbers are, even in this dire prognosis, too optimistic. It makes less optimistic assumptions about the growth of the economy, preferring not to accept the Treasury’s rose-coloured figure of 2.75 per cent. Plugging these less cheerful growth estimates into its fiscal model, the guesstimate for the cuts, if the ring-fencing is enforced, is from 18 to 24 per cent. What does that mean? According to Rowena Crawford, an IFS economist, quoted in the FT: ‘For the Ministry of Defence an 18 per cent cut means something on the scale of no longer employing the army.’ The FT then extrapolates:

At the transport ministry, an 18 per cent reduction would take out more than a third of the department’s grant to Network Rail; a 24 per cent reduction is about equivalent to ending all current and capital expenditure on roads. At the Ministry of Justice an 18 per cent reduction broadly equates to closing all the courts, a 24 per cent cut to shutting two-thirds of all prisons.

Interesante mirada sobre la crisis económica en Britannia, pero que comprende lo que está sucediendo en el resto del Viejo Mundo, en la nueva edición del London Review of Books.

De cómo la lógica del ajuste se les impone a todos – incluso a Gordon (que siempre nos cayó muchísimo más simpático que Tony) – y los números que manejan – y se honra la lógica, pero que nadie cree posible en un marco democrático – el ajuste tatcheriano aparecería al lado de éste como hecho por un populista de izquierdas –

So why all the posturing about the deficit? ‘I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or a .400 baseball hitter,’ James Carville said in the early years of the Clinton administration. ‘But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.’ It is the bond market, more than anything else, which is currently forcing the government to pretend to take the deficit seriously. This is one of the reasons for the tensions between Gordon Brown and his chancellor. Brown is allergic to the word ‘cuts’. He clearly experiences actual physical difficulty with the term, for good reason, since it does a lot to invalidate most of what he’s done in office over the last 13 years. Darling, on the other hand, has to placate the markets, and they demand a higher degree of fiscal rectitude from the UK, which means lower spending and higher taxes. If Darling doesn’t look convincing, there will be a ‘buyer’s strike’ and nobody will want to buy the many tens of billions of pounds of debt which the British government is going to have to issue over the next years. If that happens, the government will have a very serious problem. You can lie to the electorate, but you can’t lie to the bond market, which is why there will certainly be cuts, severe ones – just not quite as severe as the Texas Chainsaw Massacre scenario implied in the budget. These constraints on action are going to be in place whoever wins the election.